Ronald E Jones Trustee of the Jones Family Trust

A massive leak from one of the globe's biggest private banks, Credit Suisse, has exposed the hidden wealth of clients involved in torture, drug trafficking, coin laundering, corruption and other serious crimes.

Details of accounts linked to 30,000 Credit Suisse clients all over the globe are independent in the leak, which unmasks the beneficiaries of more than 100bn Swiss francs (£80bn)* held in i of Switzerland's best-known financial institutions.

The leak points to widespread failures of due diligence by Credit Suisse, despite repeated pledges over decades to weed out dubious clients and illicit funds. The Guardian is part of a consortium of media outlets given exclusive admission to the data.

We can reveal how Credit Suisse repeatedly either opened or maintained banking company accounts for a panoramic assortment of high-risk clients across the world.

Quick Guide Suisse secrets

Bear witness

What is the Suisse secrets leak?

Suisse secrets is a global journalistic investigation into a leak of data from the Swiss depository financial institution Credit Suisse. It comprises more than 18,000 banking company accounts that were leaked to Süddeutsche Zeitung by a whistleblower who said Swiss banking secrecy laws were "immoral". The information, which is only a partial capture of the depository financial institution's i.5 million private cyberbanking clients, is linked to more than than 30,000 Credit Suisse clients. The leak includes personal, shared and corporate bank accounts – property, on average, vii.5m Swiss francs (CHF). Near 200 accounts in the data are worth more than 100m CHF, and more than a dozen are valued in the billions. While some accounts in the information were open as far back as the 1940s, more ii-thirds were opened since 2000. Many of those were still open well into the last decade, and a portion remain open up today.

The Guardian was among more than 48 media partners around the earth including journalists at Le Monde, NDR, the Miami Herald and the New York Times. They spent months using the data to investigate the bank, in a project coordinated past Süddeutsche Zeitung and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP). They unearthed evidence Credit Suisse accounts had been used by clients involved in torture, drug trafficking, money laundering, abuse and other serious crimes, suggesting widespread failures of due diligence by the banking company. Information technology is not illegal to have a Swiss business relationship and the leak also contained data of legitimate clients who had done nothing wrong. In its response, Credit Suisse said it "strongly rejects the allegations and inferences near the bank's purported concern practices".

They include a human trafficker in the Philippines, a Hong Kong stock commutation boss jailed for bribery, a billionaire who ordered the murder of his Lebanese pop star girlfriend and executives who looted Venezuela'due south state oil company, too equally decadent politicians from Egypt to Ukraine.

One Vatican-owned account in the information was used to spend €350m (£290m) in an allegedly fraudulent investment in London property that is at the heart of an ongoing criminal trial of several defendants, including a central.

The huge trove of cyberbanking data was leaked by an bearding whistleblower to the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung. "I believe that Swiss banking secrecy laws are immoral," the whistleblower source said in a statement. "The pretext of protecting financial privacy is merely a fig leaf covering the shameful role of Swiss banks as collaborators of tax evaders."

Credit Suisse said that Switzerland's strict banking secrecy laws prevented it from commenting on claims relating to private clients.

"Credit Suisse strongly rejects the allegations and inferences nigh the bank's purported business practices," the bank said in a argument, arguing that the matters uncovered by reporters are based on "selective data taken out of context, resulting in tendentious interpretations of the bank's business conduct."

The bank as well said the allegations were largely historical, in some instances dating back to a fourth dimension when "laws, practices and expectations of financial institutions were very different from where they are now".

While some accounts in the data were open as far back as the 1940s, more than two-thirds were opened since 2000. Many of those were nonetheless open well into the terminal decade, and a portion remain open today.

The timing of the leak could hardly be worse for Credit Suisse, which has recently been aggress by major scandals. Last month, it lost its chairman, António Horta-Osório, after he twice broke Covid-nineteen regulations.

That capped an unprecedented year of controversies in which the depository financial institution became embroiled in the plummet of the supply chain finance firm Greensill Capital letter and the U.s. hedge fund Archegos Majuscule, and was fined £350m over its part in a loan scandal in Mozambique.

This month, Credit Suisse became the outset major Swiss depository financial institution in the state's history to face criminal charges – which it denies – relating to accusation it helped launder coin from the cocaine trade on behalf of the Bulgarian mafia.

However, the repercussions of the leak could be much broader than one bank, threatening a crisis for Switzerland, which retains one of the world'due south most secretive banking laws. Swiss financial institutions manage almost 7.9tn CHF (£6.3tn) in avails, near one-half of which belongs to strange clients.

The Suisse secrets project sheds a rare lite on 1 of the world'due south largest financial centres, which has grown used to operating in the shadows. It identifies the convicts and coin launderers who were able to open bank accounts, or proceed them open for years subsequently their crimes emerged. And information technology reveals how Switzerland's famed banking secrecy laws helped facilitate the looting of countries in the developing world.

Disgraced executives, fraudsters, traffickers – clients

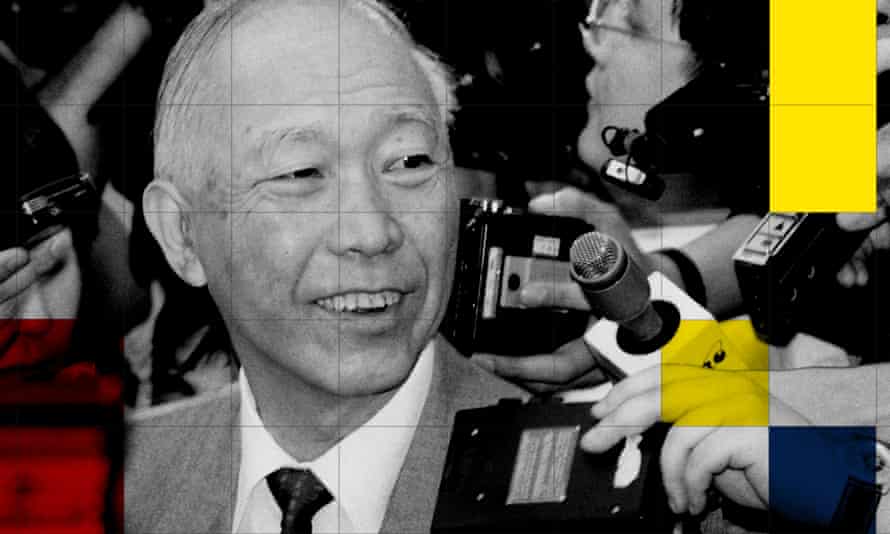

When Ronald Li Fook-shiu approached a banker to open an account in 2000, he is unlikely to have been viewed as a run-of-the-manufacturing plant client. A former chairman of the Hong Kong stock commutation, he was one of the wealthiest people in the metropolis, where he was known as the "godfather of the stock market place". Merely he was perhaps meliorate known for the time he spent in a maximum security prison.

Li's career had ended in disgrace in 1990, when he was convicted of taking bribes in commutation for listing companies on the stock exchange. However, a decade subsequently Li was nonetheless able to open an business relationship that afterward held 59m CHF (£26.3m), according to the leak.

He has since died, but his case is one of dozens discovered by reporters appearing to show Credit Suisse opened or maintained accounts for clients who had serious convictions that might be expected to show up in due diligence checks. There are other instances in which Credit Suisse may take taken quick activity afterwards red flags emerged, but the case however shows that dubious clients take been attracted to the banking company.

Similar every other depository financial institution in the world, Credit Suisse professes to have stringent command mechanisms to behave out all-encompassing due diligence on its customers to "ensure that the highest standards of conduct are upheld". In banking parlance, such controls are chosen know-your-client or KYC checks.

A 2017 leaked report commissioned past Switzerland's financial regulator shed some calorie-free on the bank'south internal procedures at that time. Clients would face intensified scrutiny when flagged equally a politically exposed person from a loftier-risk country, or a person involved in a high-run a risk activity such every bit gambling, weapons trading, financial services or mining, the report said.

Relationship managers were expected to use external sources to verify customers and their risk levels, according to the leak, including news manufactures or databases such equally the Thomson Reuters World-Check platform, which is used widely in the financial services sector to flag when people are arrested, charged, investigated or convicted of a serious crime.

Such controls might be expected to prevent a bank from opening accounts for clients such every bit Rodoljub Radulović, a Serbian securities fraudster indicted in 2001 by the U.s.a. Securities and Exchange Commission. However, the leaked information identifies him every bit the co-signatory of two Credit Suisse company accounts. The first was opened in 2005, the twelvemonth after the SEC had secured a default judgment against Radulović for running a pump-and-dump scheme.

One of Radulović's company accounts held 3.4m CHF (£ii.2m) before they closed in 2010. He was recently given a 10-year prison house sentence past a court in Belgrade for his part trafficking cocaine from Southward America for the organised crime boss Darko Šarić. Radulović's lawyer did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Due diligence is non merely for new clients. Banks are required to continually reassess existing customers. The 2017 report said Credit Suisse screened customers at least every three years and equally often as once a yr for the riskiest clients. Lawyers for Credit Suisse told the Guardian these periodic reviews were introduced "more xv years ago", meaning it was continually running due diligence on existing clients from 2007.

The bank might, therefore, have been expected to have discovered that its German client Eduard Seidel was convicted of bribery in 2008. Seidel was an employee of Siemens. As the multinational's lead in Nigeria, he oversaw a campaign of industrial-scale bribery to secure lucrative contracts for his employer by funnelling greenbacks to corrupt Nigerian politicians.

Later German language government raided the Munich headquarters of Siemens in 2006, Seidel immediately confessed his function in the bribery scheme, though he said he had never stolen from the company or appropriated its slush funds. His involvement in the corruption led to his name being entered into the Thomson Reuters World-Bank check database in 2007.

Nonetheless, the leaked Credit Suisse data shows his accounts were left open up until at to the lowest degree well into the last decade. At ane indicate later he left Siemens, ane account was worth 54m CHF (£24m). Seidel'south lawyer declined to say whether the accounts were his. He said his customer had addressed all outstanding matters relating to his bribery offences and wished to movement on with his life.

The lawyer did not reply to repeated invitations to explain the source of the 54m CHF. Siemens said information technology did not know about the coin and that its review of its ain cashflows shed no lite on the account.

While Credit Suisse said in its statement it could not comment on any specific clients, the depository financial institution said "actions have been taken in line with applicable policies and regulatory requirements at the relevant times, and that related bug have already been addressed".

In some instances, Credit Suisse is understood to accept frozen accounts belonging to problematic clients. Yet questions remain about how speedily the depository financial institution moved to close them.

One client, Stefan Sederholm, a Swedish estimator technician who opened an business relationship with Credit Suisse in 2008, was able to go along information technology open for two-and-a-half years later his widely reported confidence for human being trafficking in the Philippines, for which he was given a life sentence.

Sederholm's criminal offence start came to low-cal in 2009, when police in Manila raided a storefront purporting to exist the local affiliate of the Mindanao Peoples' Peace Movement, and discovered nearly 17 women in cubicles with webcams performing sex shows for strange customers. He was convicted in 2011.

A representative for Sederholm said Credit Suisse never froze his accounts and did non close them until 2013 when he was unable to provide due diligence cloth. Asked why Sederholm needed a Swiss account, they said that he was living in Thailand when it was opened, adding: "Tin can you please tell me if y'all would prefer to put your money in a Thai or Swiss bank?"

Ferdinand and Imelda pillage the Philippines

Swiss banks have cultivated their trusted reputation since equally far back as 1713, when the Corking Council of Geneva prohibited bankers from revealing details well-nigh the fortunes being deposited by European aristocrats. Switzerland presently became a revenue enhancement haven for many of the world'due south elites and its bankers nurtured a "duty of accented silence" most their clients' affairs.

The custom was enshrined in statute in 1934 with the introduction of Switzerland'southward cyberbanking secrecy constabulary, which criminalised the disclosure of client banking data to strange authorities. Within decades, wealthy clients from all over the earth were flocking to Swiss banks. Sometimes, that meant clients with something to hide.

1 of the most notorious cases in Credit Suisse'south history involved the corrupt Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos and his wife, Imelda. The couple are estimated to have siphoned as much as $10bn from the Philippines during the three terms Ferdinand was president, which ended in 1986.

It has long been known that Credit Suisse was 1 of the first banks to assist the Marcoses ravage their own state and in one infamous episode even helped them open up Swiss accounts under the fake names "William Saunders" and "Jane Ryan". In 1995, a Zurich courtroom ordered Credit Suisse and another bank to render $500m of stolen funds to the Philippines.

The leaked data contains an account that belonged to Helen Rivilla, an attorney bedevilled in 1992 for helping launder coin on behalf of Ferdinand Marcos. Despite this, she was able to open up a Swiss account in 2000, as was her husband, Antonio, who faced similar charges that were subsequently dropped.

It is hard to know how Credit Suisse could have missed the coin-laundering example linking the couple to the decadent Philippine leader, which was reported by the Associated Press. The couple, who could not be reached for comment, were able to hold about 8m CHF (£3.6m) with the bank before their accounts were closed in 2006.

I former Credit Suisse employee at the time alleges in that location was a deeply ingrained civilisation in Swiss banking of looking the other fashion when it came to problematic clients. "The bank's compliance departments [were] masters of plausible deniability," they told a reporter from the Organized Law-breaking and Corruption Reporting Project, i of the coordinators of the Suisse secrets project. "Never write annihilation downward that could expose an account that is not-compliant and never inquire a question y'all practice non want to know the answer to."

The 2000s was too a decade in which foreign regulators and tax authorities became increasingly frustrated at their inability to penetrate the Swiss financial system. That inverse in 2007, when the UBS banker Bradley Birkenfeld voluntarily approached US authorities with information nearly how the bank was helping thousands of wealthy Americans evade tax with secret accounts.

Birkenfeld was viewed as a traitor in Switzerland, where banking whistleblowers are often held in contempt. However, a wide-ranging United states of america Senate investigation later uncovered the aggressive tactics used by UBS and Credit Suisse, the latter of which was found to have sent bankers to high-finish events to recruit clients, courted a potential client with free gold, and in i example fifty-fifty delivered sensitive depository financial institution statements hidden in the pages of a Sports Illustrated mag.

The revelations sent shock waves through Switzerland's fiscal sector and enraged the Us, which pressured Switzerland into unilaterally disclosing which of its taxpayers had secret Swiss accounts from 2014. That same year, Switzerland reluctantly signed upwards to the international convention on the automatic substitution of cyberbanking Data.

By adopting the and then-called common reporting standard (CRS) for sharing tax information, Switzerland in effect agreed that its banks would in the time to come exchange information virtually their clients with tax authorities in strange countries. They started doing so in 2018.

Membership of the global exchange organization is oft cited past Switzerland's cyberbanking industry every bit a turning signal. "In that location is no longer Swiss bank client confidentiality for clients abroad," the Swiss Bankers Association told the Guardian. "We are transparent, there is goose egg to hide in Switzerland."

Switzerland'south most 90-twelvemonth-erstwhile cyberbanking secrecy law, however, remains in forcefulness – and was recently broadened. The Revenue enhancement Justice Network estimates that countries around the earth collectively lose $21bn (£15.4bn) each year in revenue enhancement revenues because of Switzerland. Many of those countries will be poorer nations that have not signed up to the CRS data exchange.

More than than 90 countries, nigh of which are in the developing world, remain in the dark when their wealthy taxpayers hide their coin in Swiss accounts.

This inequity in the system was cited by the whistleblower behind the leaked data, who said the CRS system "imposes a disproportionate financial and infrastructural burden on developing nations, perpetuating their exclusion from the organization in the foreseeable hereafter".

"This situation enables corruption and starves developing countries of much-needed tax revenue. These countries are the ones that therefore suffer most from Switzerland's reverse-Robin-Hood stunt," they said.

The whistleblower best-selling that the leak would contain accounts that were legitimate and declared by the client to their tax authority.

"I am aware that having an offshore Swiss bank account does not necessarily imply tax evasion or any other fiscal offense," they said. "However, it is probable that a significant number of these accounts were opened with the sole purpose of hiding their holder's wealth from financial institutions and/or avoiding the payment of taxes on majuscule gains."

Information technology was not possible for journalists in the Suisse secrets project to plant how many of the more than 18,000 accounts in the leak were alleged to relevant tax regime.

Quick Guide Suisse secrets media partners

Prove

Suisse secrets media partners

Media partners and journalists who participated in the Suisse secrets investigation, which was coordinated by Süddeutsche Zeitung and the OCCRP:

The Guardian: David Pegg, Kalyeena Makortoff, Martin Chulov, Paul Lewis, Luke Harding; Süddeutsche Zeitung: Ralf Wiegand, Jörg Schmitt, Bastian Obermayer, Frederik Obermaier, Hannes Munzinger, Mauritius Much, Emilia Garbsch, Nina Bovensiepen, Sophia Baumann; OCCRP: James Thousand Wright, Erin Klazar, Juliet Atellah, Olgah Atellah, Kira Zalan, Mohamed Ebrahem, Amra Džonlić Zlatarević, Martin Young, Jonny Wrate, Julia Wallace, Sharad Vyas, Jurre van Bergen, Alina Tsogoeva, Beauregard Tromp, January Strozyk, Tom Stocks, Graham Stack, Karina Shedrofsky, Khadija Sharife, Sana Sbouai, Paul Radu, Miranda Patrucic, Stelios Orphanides, James O'Brien, Ahmad Noorani, Marking Nightingale, Volition Neal, Eli Moskowitz, Ilya Lozovsky, Erin Klazar, Peter Jones, Mathias J, Maha All Rashid, Kevin Hall, Kai Evans, Eduardo Goulart, Misha Gagarin, Brian Fitzpatrick, Jared Ferrie, Alex Dziadosz, Stevan Dojčinović, Romina Colman, Umar Cheema, Lindita Cela, Birgit Brauer, Natalia Abril Bonilla, Eric Barrett, Antonio Baquero, Abdulwahed Al, Marking Anderson; Le Monde: Madjid Zerrouky, Faustine Vincent, Maxime Vaudano, Joan Tilouine, Thomas Saintourens, Anne Michel, Benjamin Barthe, Jérémie Baruch; NDR: Julia Wacket, Benedikt Strunz, Elena Kuch, Antonius Kempmann, Volkmar Kabisch, Johannes Jolmes, Lisa Maria Hagen, Lena Gürtler; New York Times: Ben Hubbard, David Enrich, Jesse Drucker; Miami Herald: Ben Wieder, Jay Weaver, Casey Frank, Antonio Delgado, Shirsho Dasgupta, Aaron Albright; CIN: Mirjana Popovic, Jelena Jevtić, Mubarek Asani, Aladin Abdagic; Trece Republic of costa rica Noticias: Mercedes Agüero R; Irpimedia: Lorenzo Bagnoli, Cecilia Anesi; Slidstvo_info: Yanina Korniienko, Anna Babinecs; Alqatiba: Walid Mejri, Rahma Behi; WDR: Massimo Bognanni; Investico: Karlijn Kuijpers, Romy van der Burgh; IRL: Bojan Stojanovski, Ivana Nasteska, Aleksandra Denkovska, Maja Jovanovska, David Ilieski, Saska Cvetkovska, Trifun Sitnikovski, Denica Chadikovska; Reporter.lu: Laurent Schmit, Luc Caregari; Le Soir: Joël Matriche, Xavier Counasse; SVT: Johan Wikén, Aris Velizelos, Joachim Dyfvermark; Twala.info: Lyas Hallas; The Confluence: Josy Joseph; Armando.info: Roberto Deniz, Patricia Marcano, Joseph Poliszuk, Ewald Scharfenberg, Valentina Lares; profil: Michael Nikbakhsh, Stefan Melichar; Interferencia de Radioemisoras UCR: Hulda Miranda; Diario Rombe: Delfín Mocache; La Stampa: Gianluca Paolucci; Expresso: Micael Pereira; Krik: Dragana Pećo. Infolibre: Manuel Rico; Infobae: Sandra Crucianelli, Mariel Fitz Patrick, Iván Ruiz; La Nación: Hugo Alconada Mon; Libya: Rami Salim; Efecto Cocuyo: Laura Weffer; Hetq: Samson Martirosyan, Edik Baghdasaryan; Prachatai: Yiamyut Sutthichaya, Rattanaporn Khamenkit; Africa Uncensored: John; Dépêches du Republic of mali: David Dembele; Premium Times: Idris Akinbajo, Dapo Olorunyomi; Gambia: Marr Nyang; Verdade: Aderito Caldeira; The Namibian: Shinovene Immanuel; NewsHawks: Dumisani Muleya; L'Evenement: Moussa Aksar; Impact.sn: Momar Dieng.

Media partners in the consortium wrote to more than 100 Credit Suisse clients in the information, request whether they had disclosed their Swiss accounts to taxation authorities. Five confirmed they had done and so. Six said they were not required to declare their Swiss accounts. No others replied.

Links to some other dictator … and another

Ferdinand Marcos may have been Credit Suisse'south most notorious customer. He is arguably rivalled simply past relatives of the fell Nigerian dictator Sani Abacha, who is believed to take stolen as much as $5bn from his people in just half-dozen years. It has long been known that Credit Suisse provided services to Abacha's sons, opening Swiss accounts in which they deposited $214m.

Credit Suisse was publicly contrite after being kicked off a sustainable investment alphabetize over the affair. "We understand that the alphabetize was not actually happy with u.s. being involved with Abacha – nosotros were not happy ourselves," a spokesperson said in 1999. "Merely we have addressed those problems and for several years we accept taken internal measures to brand sure zero similar happens in the future."

Banks that enable kleptocrats to launder their coin are complicit in a particularly far-reaching crime. The consequences for already impoverished populations can be devastating, as country coffers are siphoned, basic standards are eroded and trust in democracy plummets.

Politicians and state officials are amidst the riskiest customers for banks considering of their access to public funds, especially in developing nations with fewer legal safeguards against corruption. Banks and other financial institutions are required to subject politically exposed persons, or PEPs, to the most stringent checks, known as "enhanced due diligence".

The leaked Credit Suisse data is brindled with politicians and their allies who have been linked to corruption before, during or after they had their accounts. None are besides known as the Marcoses or the Abachas, but several wielded peachy power in countries from Syria to Republic of madagascar, where they amassed personal fortunes.

They include Pavlo Lazarenko, who served a corrupt single year every bit prime government minister of Ukraine between 1997 and 1998 earlier applying for an business relationship at Credit Suisse. One month subsequently force per unit area from rivals forced Lazarenko to announce his resignation, he opened his get-go of ii Credit Suisse accounts. One was later valued at almost 8m CHF (£3.6m).

Lazarenko was subsequently estimated by Transparency International to have looted $200m from the Ukrainian government, allegedly past threatening to harm businesses unless they paid him 50% of their profits. He pleaded guilty to coin laundering in Switzerland in 2000, and was subsequently indicted in the US for abuse and sentenced to ix years in prison in 2006 in relation to bribes received from a Ukrainian businessman.

His lawyer said those convictions did not relate to the theft of any money from the people of Ukraine. Lazarenko, who reportedly lives in California, has resisted returning to the country, where he still faces accusations he stole $17m. His lawyer said his Credit Suisse accounts had not been accessed for 2 decades and were frozen in connection with court proceedings against him.

Information technology remains unclear why Credit Suisse allowed Lazarenko to open up an account and deposit such huge sums in the first place, given his groundwork; earlier entering politics, Lazarenko was a functionary in charge of a collective farm.

Monika Roth, an expert on money laundering and a professor at Lucerne University, said Swiss banks had for a long fourth dimension struggled to properly challenge politicians and public officials who, subsequently stints in public office on relatively modest salaries, turned up with huge sums to deposit. She said: "Nobody wants to accept asked the question: how is that possible?"

Around the time information technology was doing business with Lazarenko, Credit Suisse appears to accept too made inroads into the Egyptian political institution under the dictator Hosni Mubarak, who was president for three decades until 2011. The bank's clients included Mubarak's sons, Alaa and Gamal, who established business empires in Egypt.

The brothers' human relationship with the depository financial institution spanned decades, with the earliest joint account opened past the brothers in 1993. Past 2010 – the year before the popular revolt that ousted their father – an account belonging to Alaa held 232m CHF (£138m).

After the Arab bound uprisings their fortunes inverse, and in 2015 the brothers and their male parent were sentenced to three years in jail by an Egyptian court for embezzlement and abuse. They say the case was politically motivated, but later on an unsuccessful entreatment Alaa and Gamal paid an estimated $17.6m to the Egyptian government in a settlement understanding that made no admissions of guilt.

Lawyers for the brothers reject any suggestion they were corrupt, saying their rights were violated during the Egyptian instance, and x years of wide-ranging and intrusive investigations into their global assets past strange authorities has non uncovered any legal violations. They added that their Swiss accounts had been frozen for over a decade, pending the resolution of investigations by the Swiss authorities.

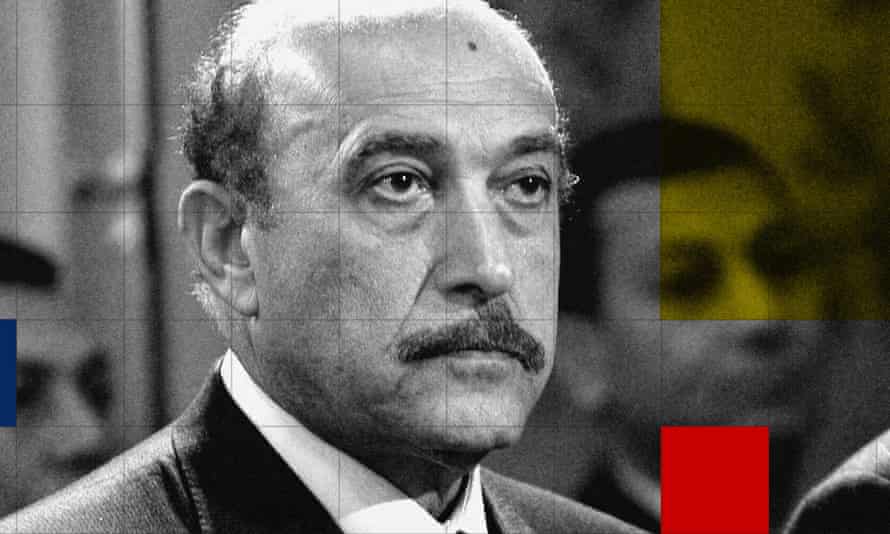

Other Credit Suisse clients linked to Hosni Mubarak were the belatedly tycoon Hussein Salem – who acted as a fiscal consigliere for the dictator for virtually three decades, amassed a fortune through preferred tender deals and died in exile subsequently facing money-laundering charges – and Hisham Talaat Moustafa, a billionaire politician in Mubarak'southward political party.

Moustafa, who could not exist reached for comment, was bedevilled in 2009 of hiring a hitman to murder his ex-girlfriend, the Lebanese pop star Suzanne Tamim – merely his account was not closed until 2014.

Another Mubarak henchman linked to Credit Suisse's banking services was his former spy chief Omar Suleiman. His associates are listed in the information equally benign owners of an account that held 63m CHF (£26m) in 2007. Suleiman was a feared figure in Egypt, where he oversaw widespread torture and human rights abuses.

The information reveals Credit Suisse accounts held past several more intelligence and military machine figures and their family members, including in Pakistan, Jordan, Yemen and Iraq. One Algerian client was Khaled Nezzar, who served equally government minister of defence until 1993 and participated in a insurrection that precipitated a cruel civil state of war in which the military junta he was office of was defendant of disappearances, mass detentions, torture and execution of detainees.

Nezzar's alleged role in human rights abuses had been widely documented past 2004, when his account was opened. It contained a maximum balance of 2m CHF (£900,000) and remained open until 2013, two years subsequently he was arrested in Switzerland for suspected war crimes. He denies wrongdoing and the investigation is ongoing.

If ordinary Algerians, Egyptians and Ukrainians have reason to complain that Credit Suisse may accept aided nefarious leaders, their grievances stake in comparison with Venezuelans.

Reporters working on the Suisse secrets project identified Credit Suisse accounts linked to nearly ii dozen business people, officials and politicians implicated in corrupt schemes in Venezuela, most of which revolved around the state oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA).

"Corruption has always been around in PDVSA, in varying degrees and levels," said César Mata-Garcia, an bookish at the University of Dundee specialising in international petroleum law. "The words 'Venezuela', 'PDVSA' and 'oil' are an warning bell for banks."

If and then, that does not appear to have stopped Credit Suisse acquiring clients subsequently revealed to be involved in numerous US investigations and prosecutions linked to PDVSA and the looting of the Venezuelan economy.

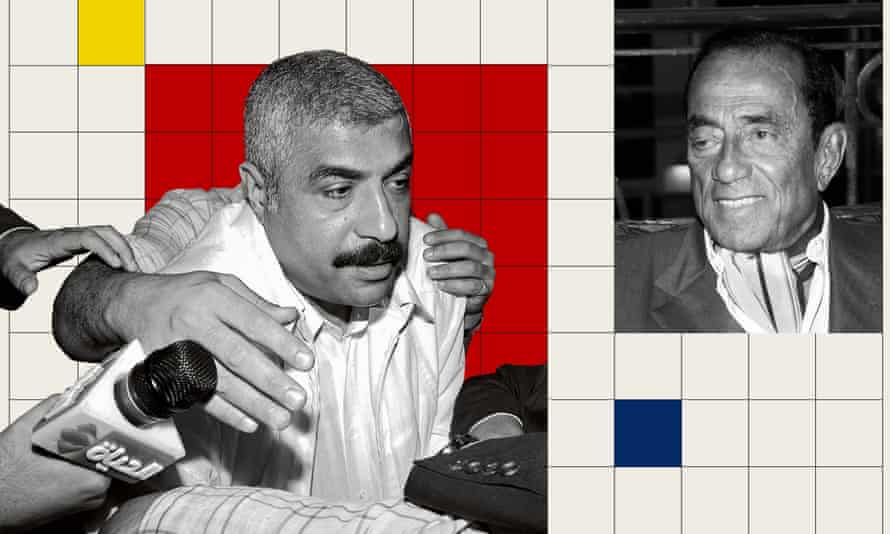

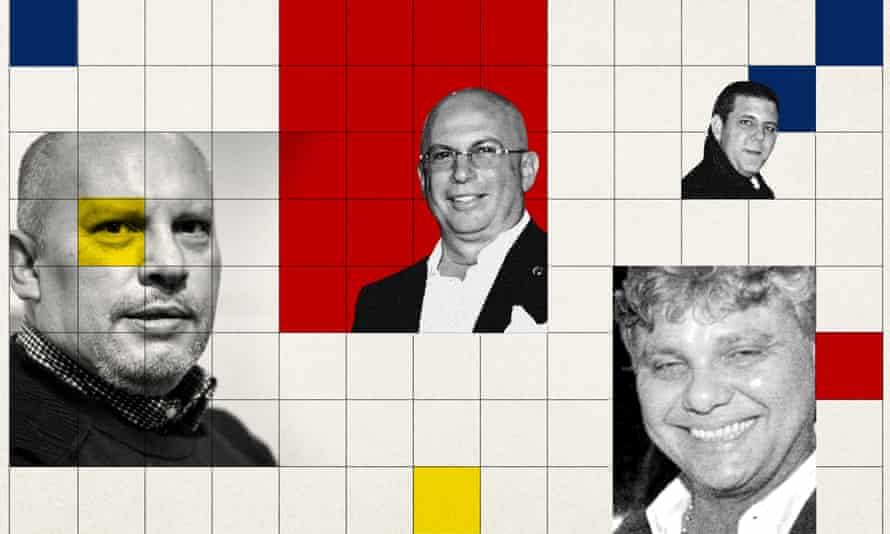

One case involves two Us-based businessmen with Venezuelan connections, Roberto Rincón Fernández and Abraham Shiera Bastidas, who in 2009 ready about bribing officials in exchange for lucrative PDVSA contracts with the help of an associate, Fernando Ardila Rueda. Amidst those who allegedly received bungs were the energy vice-government minister, Nervis Villalobos Cárdenas, and a senior PDVSA official, Luis De Léon Perez.

In 2015, The states prosecutors began indicting the participants; court papers make repeated reference to payments into accounts in an unnamed Swiss bank. However, the leaked data reveals all five men had Credit Suisse accounts agile at the time of the offences. Of the five, 4 take pleaded guilty. The exception, Villalobos, is resisting extradition to the US from Kingdom of spain.

Some of the Venezuela-linked Credit Suisse accounts contained enormous sums; Villalobos had as much as 9.5m CHF (£six.3m) in his account and De Léon had as much every bit 22m (£15.5m). Rincón, the man of affairs paying their bribes, had more than 68m CHF (£44.2m) in his business relationship as of Nov 2015, the month prior to his abort.

'How many rogue bankers earlier you lot go a rogue bank?'

When Credit Suisse's ornate headquarters were constructed in the 1870s in Zurich, they were designed to symbolise "Switzerland as a financial centre". More than 150 years later, Credit Suisse occupies the aforementioned yard bounds and Switzerland remains a global offshore centre, much as it has done for the last 300 years.

It is only in recent decades that Credit Suisse, one of Switzerland's oldest and most cherished banks, acquired its reputation for cataclysm. As 1 commentator observed earlier this week: "The bank boasts that its purpose is to serve its wealthy clients 'with care and entrepreneurial spirit', merely at this stage about of them would probably be happy if it could just avoid yet some other major scandal."

Horta-Osório lasted less than a twelvemonth earlier resigning last month. Soon after Credit Suisse appointed its new chairman, Axel Lehmann, the bank reported a loss of 1.6bn CHF (£1.3bn) in the fourth quarter, in office because information technology had put aside more than than 400m CHF (£320m) to deal with unspecified "legacy litigation matters".

And in that location is no shortage of those. The scandals involving Greensill, Archegos and Mozambique bonds take dogged the banking concern over the past year.

Over the past three decades, Credit Suisse has faced at least a dozen penalties and sanctions for offences involving tax evasion, money laundering, the deliberate violation of U.s.a. sanctions and frauds carried out against its own customers that span multiple decades and jurisdictions. In full, it has racked up more than $4.2bn in fines or settlements.

That includes the $two.6bn the Swiss bank agreed to pay US regime after pleading guilty to conspiring to assistance tax evasion in 2014; the $536m information technology was fined by the U.s.a. five years before for deliberately circumventing United states of america sanctions confronting countries including Iran and Sudan in 2009, and other payouts to Germany and Italy over tax evasion allegations.

Against this backdrop, the Suisse secrets revelations may fuel questions over whether Credit Suisse'southward challenges are indicative of a deep malaise at the banking company.

Jeff Neiman, a Florida-based attorney who represents a number of Credit Suisse whistleblowers, believes the sheer number of scandals involving the bank indicates a deeper problem.

"The bank likes to say it's just rogue bankers. Just how many rogue bankers do y'all need to have before you start having a rogue bank?" he said. Neiman alleges there has been a civilisation at the bank "which encourages its bankers probably from the top down to hear no evil, meet no evil, speak no evil, coffin their heads in the sand on a good day, and on many days, actively assist folks to skirt whatsoever the law may be in social club to best protect assets nether management"."

Such allegations are strongly rejected past Credit Suisse. "In line with financial reforms across the sector and in Switzerland, Credit Suisse has taken a series of significant additional measures over the last decade, including considerable further investments in combating financial crime," the depository financial institution said in its statement, adding that information technology upheld "the highest standards of behave".

Its lawyers said it had fully cooperated with many of the investigations cited past the Guardian and that any by individual failings by the banking concern did not reflect its current business policies, practices or culture. In November, it announced it would put "risk management at the very core of the bank".

The bank said its "preliminary review" of the accounts flagged by the Suisse secrets reporting project had established that more than ninety% of those reviewed were now closed or "were in the process of closure prior to receipt of the printing inquiries". Of the remaining accounts, which remain agile, the banking concern said it was "comfortable that advisable due diligence, reviews and other command-related steps were taken, including pending account closures".

The Credit Suisse statement added: "These media allegations appear to be a concerted effort to discredit the bank and the Swiss financial marketplace, which has undergone significant changes over the terminal several years."

The debate over whether Switzerland'due south banking industry has undergone sufficient reforms is likely to be renewed in light of the leak. The whistleblower who shared the data suggested that banks alone should non exist blamed for the state of diplomacy, as they are "merely existence good capitalists by maximising profits within the legal framework they operate in".

"Simply put, Swiss legislators are responsible for enabling fiscal crimes and – past virtue of their direct republic – the Swiss people have the ability to do something about it. While I am aware that banking secrecy laws are partly responsible for the Swiss economic success story, it is my strong opinion that such a wealthy state should be able to afford a conscience."

* Currency conversions are based on historical rates.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2022/feb/20/credit-suisse-secrets-leak-unmasks-criminals-fraudsters-corrupt-politicians

0 Response to "Ronald E Jones Trustee of the Jones Family Trust"

Post a Comment